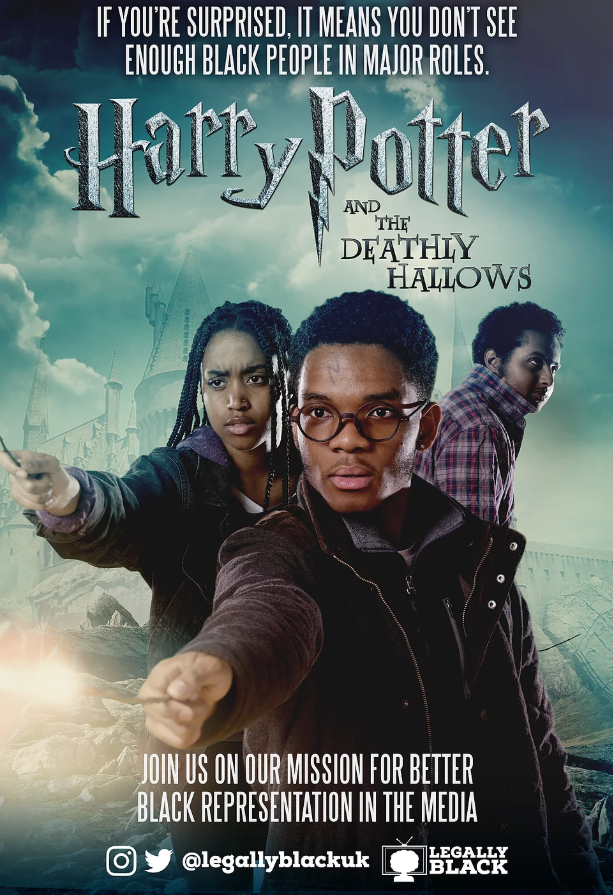

When London-based activists Legally Black put up bus-stop posters of unknown black ‘actors’ featuring in blockbuster movies such as Harry Potter, jaws dropped at the simple power of the message, and minds were changed even as headlines were made. The activists were telling the world ‘We want to see characters that look like us. We’re here.’

This was a triumph for non-white film lovers that aimed to enrich the creative output enjoyed by all film lovers. Book lovers are often open to exploring otherness and enjoy the chance to empathise with the interior lives of unknown people to a degree that only literature truly allows. Most book lovers have long desired to engage with a variety of races, cultures, genders, ages and experiences. What has changed in recent years is that certain innovators within publishing – including 4th Estate – have actively sought to ensure that this rich diversity is represented in the books we read.

Most authors, a band that obviously includes many a keen student of ‘otherness’, have embraced this drive (and only a few of them while clucking that – surely now somewhat tiresome – caveat ‘provided that standards don’t drop’, as if they necessarily must when black authors take their place at the table). But as authors, we must not now be side-tracked, or intimidated into believing that we need to simply ‘represent’ or ‘inspire’ or just ‘see ourselves reflected’ (although all of that is true) more than we need to serve the demands of ideas, of our stories and of literature. Whatever our colour and whatever the background of our characters, we must fully engage in the wider cultural, intellectual and socio-political conversation.

It is true to say that some baulk at representing people of colour in any way other than in an unerringly positive light. Naturally, when one has to process some of what is put out about the African-Caribbean and other ethnicities in these times, it is easy to feel a desire to push back against a certain shame. If we are older, wiser or luckier we may feel anger rather than shame. Even so, it can be tempting to over-compensate. Accentuating the positive is understandable when we have been beaten over the head (sometimes literally) thanks to the widespread hostile presentation of black people in certain sections of the media, or forced to face the fact that while 2.7% of the UK population is black, black people make up 13.7% of the prison population, or are told yet again that black Britons are not destined for the loftiest academic heights. Surely black authors must do everything in their power to overturn such assumptions at once, beyond simply existing? This may seem a powerful argument and yet I believe that the knee-jerk instinct urging authors to write only good, simple, harmless black characters must be passionately resisted.

Yes, we do need heroes and role models, and plenty of them. This may be most desirable within the world of children’s books. As WeNeedDiverseBooks.org states on its homepage, ‘Imagine a world in which all children can see themselves in the pages of a book’. Yes, here’s to that world. Such drives as have doubtless helped encourage publishers to put out a greater range of books that reflect more of our population in all its variegated magnificence. However, as an author I wish to populate my works with all manner of people, who, regardless of their colour, exhibit flaws and complexities and assorted weird tics, emotional scars, insecurities and idiosyncrasies. I wish to write characters who are as complex and unpredictable as those that white male authors of literary fiction have been moved to write – and felt at liberty to write – since literature first began.

If authors stay attuned to our best literary instincts we will take this truer path. I refuse to make my characters ‘tap dance’. Beyond my debut novel, Darling, I wish to write about the strange, the tragic, the beautiful the disturbing and the redemptive … in short, about all the ever-playing light and shade, sameness and otherness that dances within characters in such a way that they invite us to more closely examine ourselves. These rare creatures must be more than good, or bad; written true they might just be iconic. If we don’t attempt to grasp such truths as authors, however we identify as individuals, then we can only be failing at one of our most important literary tasks.

A wise author wants to attract all readers, including those who may see themselves reflected in the pages of their own book – African, Caribbean, Caucasian and all manner of ‘other’. I hope never to infantilise my readers by offering up only paragons and role models. Nor do I wish to produce conventional, convenient, plastic monsters – a more obvious failing. I write for all adults and, at the same time, black readers are not children.

Literature that features black, Asian and minority ethnic characters needs – deserves – to boast its fair share of sinners, lovers, criminals, fallen angels and unlikely heroes. Anything less would be more than a missed opportunity for an author, it would be a dereliction of one’s creative duty. If some of the most popular books of all time can feature Tom Ripley or Becky Sharp or the main characters in Trainspotting, or Hannibal Lecter, or the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, or John Self, then books featuring characters of colour can dare too.

No author, then, must be tempted to oversimplify their BAME characters in well-meaning efforts to engender feelings of empathy and engagement. The greatest of the black American writers have long understood this, as we see in characters from Sethe in Toni Morrison’s Beloved, to Cora in Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, to Celie in The Color Purple, to Me of Paul Beatty’s The Sellout. These books deliver unforgettable, multi-layered, multi-dimensional, multi-directional characters to do justice to the complexity of the African-American experience, steeped deep as it is in the still-raw history of racial conflict and tribulation.

As black British authors attempt to explore our collective identity – in part shared, in part composed of at least 1.9 million experiences, the uniqueness of which must be recognised – we also need to be led above all by ideas. We do need a few dark-skinned Pollyannas battling their way through the world, but in this country, in these times, I think we also need to reflect all the darkness and danger that comes with careering towards this unknown cliff-edge that Brexit might represent.

This was why I wrote Darling, a novel about a bitter feud between a black woman and her white stepdaughter. Above all, I wanted to explore how racism corrupts love. Darling White, a black British nurse, represents love that has been taken for granted for too long, a little like the Caribbean nurses who came over to these isles as part of the Windrush Generation. Darling is a dark novel without any clear role models, and without a happy ending. But, heroine or anti-heroine, Darling is a true distillation of her past and she shapes her complex, imperfect present as forcefully as any white male protagonist. Her flaws make her fate and, as an author, a reader, a black British woman and doubtless as a flawed-but-human being, I stand by the imperfections that life has wrought within her. More than that, I am profoundly glad that Darling has been encouraged to speak up from within this country’s diverse and ever-changing literary landscape, just as she is, in these times. For anyone who believes in the prodigious power of fiction, that may be what matters most.

Follow Rachel on Twitter and Instagram.

Darling is out now.

4thestatebooks