Alan Garner is a writer who has sought the fantastical within the ordinary, finding magic and menace in the local landscapes and folklore of the Cheshire plains in the north west of England. Having embedded himself in Alderley Edge, the main setting for a variety of his award-winning books, Garner has come to embody the “spirit of place” with his unmatched knowledge of the area’s folklore, archaeology and history.

Read below as writer Dr. Adam Scovell explores the use of landscape in Garner’s fiction, beginning with his “Weirdstone trilogy” and examining how he blurs the real and the imaginary to create an uncanny realm that feels eerily familiar.

Can the land remember us?

When we consider a landscape, does that landscape in turn consider us?

Is our place in a landscape defined by our time and actions spent within it or does this relationship actually work the other way round, perhaps instead always to forever ghost our ancestors?

Throughout his writing career, Alan Garner has dedicated many books to quietly addressing these questions. Under the guise of the fantastical, at the heart of all Garner’s work lies a sense of place seeping into our consciousness. This isn’t a narrative device or a thematic strain so much as a channelling of lived experience. More than most British writers, Garner has lived the places of his books. He has spent the majority of his life in and around Alderley Edge in Cheshire, predominantly in Congleton under the shadow of the Lovell Telescope dish of Jodrell Bank. It is a place imbued with strange tales and folklore, where the cosmic and the archaic intertwine with ease. Almost uniquely in terms of detail, Garner’s roots are deeply embedded into the settings of his many novels, giving him a clear and precise insight into the history, folklore and craft of a specific place that few peers can match.

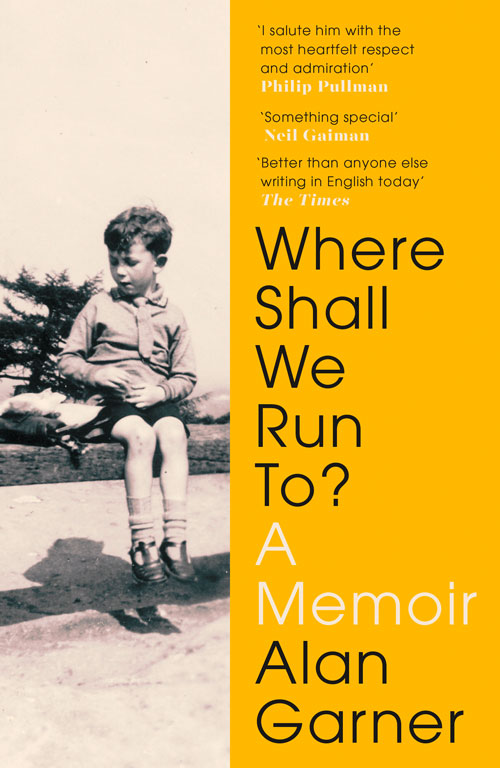

In particular, Garner has been fixated on the Edge of Alderley; a stone precipice that provides sweeping views out over the Cheshire plains, all of the way to Manchester when the skies are clear. From his debut novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960) to his very latest memoir, “Where Shall We Run To?”, place is fixed, not simply to set the scene or to provide a backdrop for some action or drama, but because it defines everything in Garner’s work. His prose is carved out of rock and wood, giving the impression that it has always been here, and continuing the tradition of his craftsmen heritage. On a stone wall near the house of his birth, his forefather’s name is cut into the stone, a signature for a modest masonry achievement and a call from those who were once there. Garner’s prose is the same, modest signature etched with beautiful lucidity through the elements; of the land remembered and of the remembering land.

Remembering the Land

“When I was not confined to the house, I would spend my days and my nights on the Edge.” (The Voice That Thunders)

Especially in his fiction work, Garner places land on par with character. In The Owl Service (1967), for example, the majority of the book is taken up either with dialogue or place description. A good example is this simple but beautiful short passage: “Alison sat in the shade of the Stone of Gronw among the meadowsweet. Clive stood in the river.” This binary allows for a melding of inner and outer worlds, meaning the reader can see quite plainly how place slowly becomes pivotal to the lives of the characters. Characters rarely fail to mention or imply some aspect of location: the roads, routes, hills, forests, peaks and fields that surround them. They remember the land even when they wish to forget it.

Considering a memoir by the writer is an intriguing proposition, if only because his previous work has often been drenched in his biography and the place that coloured it. Susan and Colin of the Weirdstone Trilogy walk the same paths that Garner walked with his father; around the Edge, up to Stormy Point and past the various wells that litter the path. One in particular stands out, the “Wizhard’s Well,” as it is rumoured that Garner’s great, great grandfather carved the face of a wizard onto that rock; the same wizard who would eventually turn up as Cadellin Silverbrow in The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. As he wrote in that book:

“Just as they were about to turn for home after a climb from the foot of the Edge, the children came upon a stone trough into which water was dripping from an overhanging cliff, and high in the rock was carved the face of a bearded man…”

The passage could easily be from “Where Shall We Run To?” with its detail gleaned from memory. It is fitting that a similar narrative of wandering there with his father finds its way into his latest work. If anything is remembered from Garner’s past it is almost always enshrined in place. Even when his emotions are the overriding element being summoned, as in his novel Red Shift (1973) where inner turmoil transcends time, the emotions are almost always remembered and preserved in place like an insect in amber.

The Land Remembering

In an essay taken from The Voice That Thunders, Garner writes of the Edge that it “…both stopped, and melted time.” In his fiction and his essay writing, the landscapes of Cheshire, Wales and Alderley has potential sentience: if his characters at any point do forget the importance of the place around them, then the place will do its utmost to remind them. Alison of The Owl Service and her frustration at being stuck on holiday in the Mawddwy Valley is a good example of this, as is Ian in Thursbitch (2004) who is reluctant to leave the ailing Sal to the mercy of the temporally permeable Pennines landscape. Since Garner wrote Red Shift, temporal shifts have sat predominantly in the landscapes of his writing, often hinting towards some sort of agency. The three male characters of Red Shift, Ian and Sal of Thursbitch and even William Buckley of Strandloper (1996), are all partaking in some unspoken communion with the terrain around them, as if the past filtering in allows access to some deeper truth.

Reading Garner’s nonfiction, this is clearly reflective of his own relationship with the land and his psyche as much as an effective narrative device. In fact, to label it as the latter at all undermines what is really happening as it seems so essential to all of his post-Red Shift narratives, perhaps even being their key instigator. This is even when, as in these later novels, the elements of place painting is reduced to an absolute bare minimum. Place instead haunts through names, sometimes so intensely localised, unfamiliar and idiosyncratic to the North West that they seem possessed of incantation as much as geography. This sentience feels like a remembering, an interaction beyond exploration and normal language. It tells of an openness to place that is dangerous if unaware or dark of heart. In the same essay, Garner wrote of the Edge that:

“It is physically and emotionally dangerous. No one born to the Edge questions that, and we showed it proper respect.”

This respect isn’t superstitious or melodramatic. It is an acknowledgement of a heightened awareness of place in temporal terms; one that is part of a continuity with generations gone by. This past isn’t just underneath the rock and soil but constantly drifting back and forth as the land remembers, even when we briefly forget.

Where Shall We Run To? is out now.