For much of the time I was writing My Absolute Darling, I lived on the fourth floor of a falling-down apartment building in downtown Salt Lake City. In the summer, with the heat rising from the apartments below us, it could get to be 106 degrees. We had no air-conditioning, and I’d work hunched on the floor, dripping sweat, slamming redbull, and loving the work. In the winter, if I left a glass on the windowsill, it would ice over. The radiators hissed and steamed and sometimes fountained water like you were in a submarine that had just been hit. I wrote whenever I could. I had no regular hours, no desk, no place save the living room floor, no meditative rituals, no artist’s lifestyle, no coffeehouses I frequented, nothing except the work itself. I wrote whenever I wasn’t in the backcountry and wasn’t at the restaurant. I tried to keep my hours at the restaurant down to thirty a week, and I tried to write for thirty or forty more, which meant getting up and getting straight to the keyboard and working hard throughout the day if I was to have any chance of getting out climbing that night.

Now, I have a desk and a place to work, but these things are just accessories and can never substitute for your love of the writing, which is the heart of the matter.

I work in my office, which is an empty room with a desk and a bookshelf, a few dichotomous keys, and a microscope for grass identification. I keep it as empty as I can. The desk, which is the work a local artist who may not really know what he’s doing, is not desk-height and so I sit in a drafting chair with a window that looks out onto our shady street of Norway maples and plane trees. I keep a few reference books and a notebook of phenological observations close to hand. There are a couple of airplants on the windowsill and sometimes Norbert, our crested gecko, will curl up in one and snooze while I work.

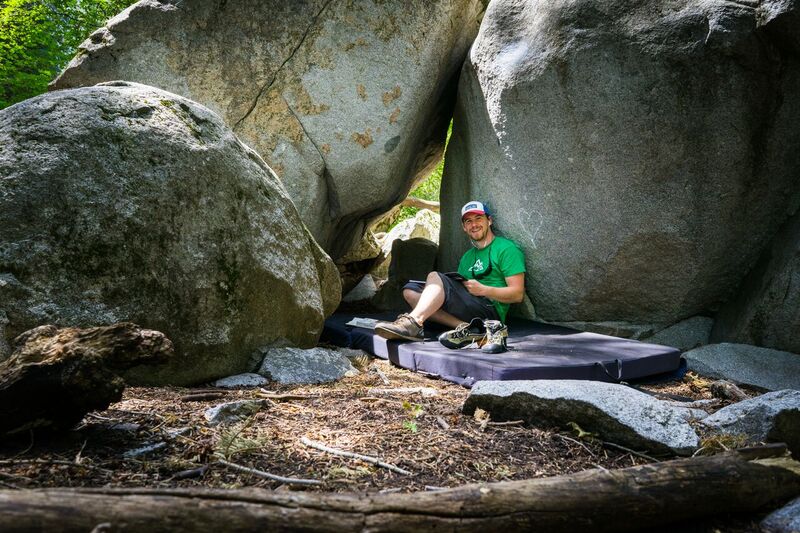

If the heat isn’t too bad, I’ll sometimes take my crash pad and hike up into the canyons with some notebooks and Woody Plants of Utah, stopping whenever I find a plant I don’t know. I’ve never had much luck with field guides, and I like how a dichotomous key requires you to slow down and really look at the plant. That is the best way to learn. It takes me three or four hours, working with a microscope, to identify a new grass, but most trees and shrubs I can track down in a few minutes. I’ll set up the crash pad at the base of a remote bouldering problem where I’m likely to be alone, and I’ll spend the day there, running laps on the bouldering problem and writing.

I drink coffee and I have few other rituals. I try and remember that the working is the thing, and anything else you might think you need to do the work, you do not need. People write while teaching, they write while raising their children, they write in straightened circumstances and while living out of cars, I don’t think the work is the less for that, I think you could write anywhere, if you want it badly enough.

Words by Gabriel Tallent

4thestatebooks